Yellowstone: Taylor Sheridan Didn’t Fix One Plot Hole Before Using It Again

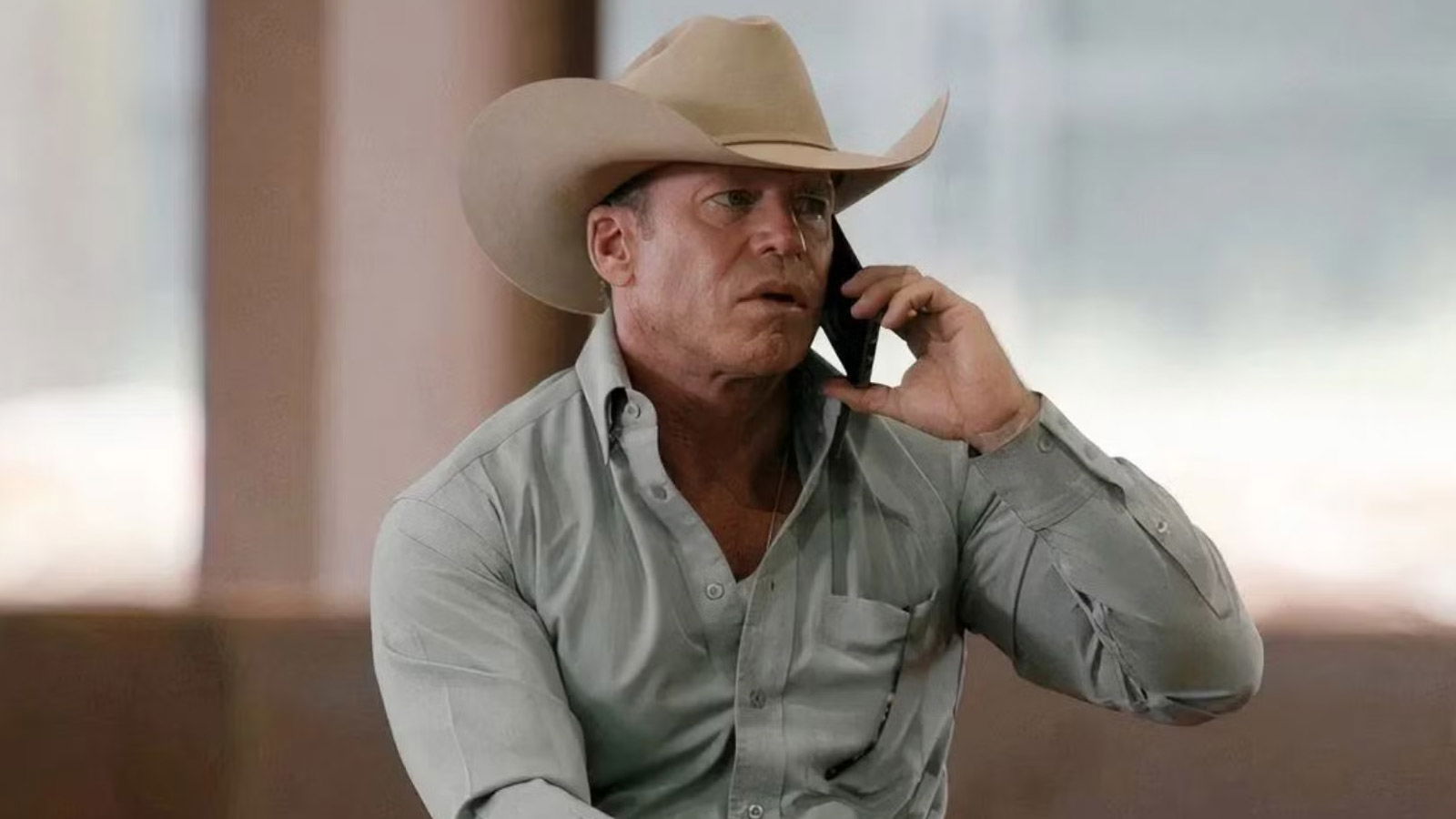

Taylor Sheridan has earned a reputation as one of television’s most influential modern storytellers by building the neo-Western universe

through Yellowstone and its many spin-offs. However, even Sheridan’s most devoted fans acknowledge a recurring flaw in his work: the tendency to introduce seemingly meaningful ideas that are quietly abandoned.

He did the same in Yellowstone, only to repeat it in his directorial effort, Those Who Wish Me Dead. In the former, there is a storyline in Season 2 involving Tate Dutton and a horse. Tate convinced his grandfather, John Dutton, to buy him a horse named Lucky.

Taylor Sheridan has earned a reputation as one of television’s most influential modern storytellers by building the neo-Western universe through Yellowstone and its many spin-offs. However, even Sheridan’s most devoted fans acknowledge a recurring flaw in his work: the tendency to introduce seemingly meaningful ideas that are quietly abandoned.

He did the same in Yellowstone, only to repeat it in his directorial effort, Those Who Wish Me Dead. In the former, there is a storyline in Season 2 involving Tate Dutton and a horse. Tate convinced his grandfather, John Dutton, to buy him a horse named Lucky.

John agrees on one condition: Tate must take responsibility for feeding, watering, and caring for the animal, framing the horse as some sort of a lesson in maturity and accountability. However, we barely see any scenes of Tate and Lucky. Instead, Tate is kidnapped by the Beck brothers shortly afterward while tending to the horse, and Lucky effectively disappears from the series.

What was supposed to be a symbol of Tate’s growth into ranch life and cowboy values ends up being an undeveloped storyline that was only supposed to serve as a catalyst in Tate’s kidnapping.

Then again, in Those Who Wish Me Dead, the child character, Connor, briefly shares a quiet, intimate moment with a horse while traveling with his father. The scene is filmed with deliberate care, emphasizing calmness, trust, and Connor’s apparent natural connection to animals.

The moment serves as symbolic, as if it will carry narrative weight in the film later. Instead, it is never revisited. The story moves forward without any payoff, rendering the scene emotionally hollow in retrospect. In both cases, Sheridan introduces a child-and-horse dynamic that feels purposeful, only to abandon it entirely.

This repeated and abandoned pattern, especially in Western storytelling, risks undermining the emotional integrity of the narrative rather than enriching it. But this seems like a mistake that Sheridan loves repeating.